Rediscovering Setauket's Indigenous Legacy: The History and Challenges of the Setalcott Nation

Setauket, New York – A picturesque hamlet on Long Island’s North Shore, often renowned by tourists and many residents alike for its ties to the Culper Spy Ring during the Revolutionary War. But another piece of history is concealed behind this well-known historical account.

Long before colonial settlements and spy rings, the men, women and children of the Setalcott Nation walked the land. They are Setauket’s namesake: their history intricately woven into Long Island’s fabric.

Understanding their legacy goes beyond being familiar with local history. It helps ensure that the rich tapestry of Indigenous cultures on Long Island remains an integral part of our historical and cultural roots.

Despite their enduring presence, the tribe continues to fight for federal recognition today — a paramount step to secure access to essential resources and ensure Setalcott descendants always have a rightful place on their ancestral land.

The importance of understanding their legacy goes beyond being well-versed in local history, but ensuring the rich tapestry of the indigenous cultures present long before us remains an integral part of Long Island’s historical and cultural roots.

Despite their enduring presence, today, descendants of the Setalcott continue to fight for federal recognition: a paramount step in securing not only their rightful place in Long Island’s history but to ensuring access to essential resources and that their descendants always have a place on the land as its forebearers.

Origins of the Setalcott

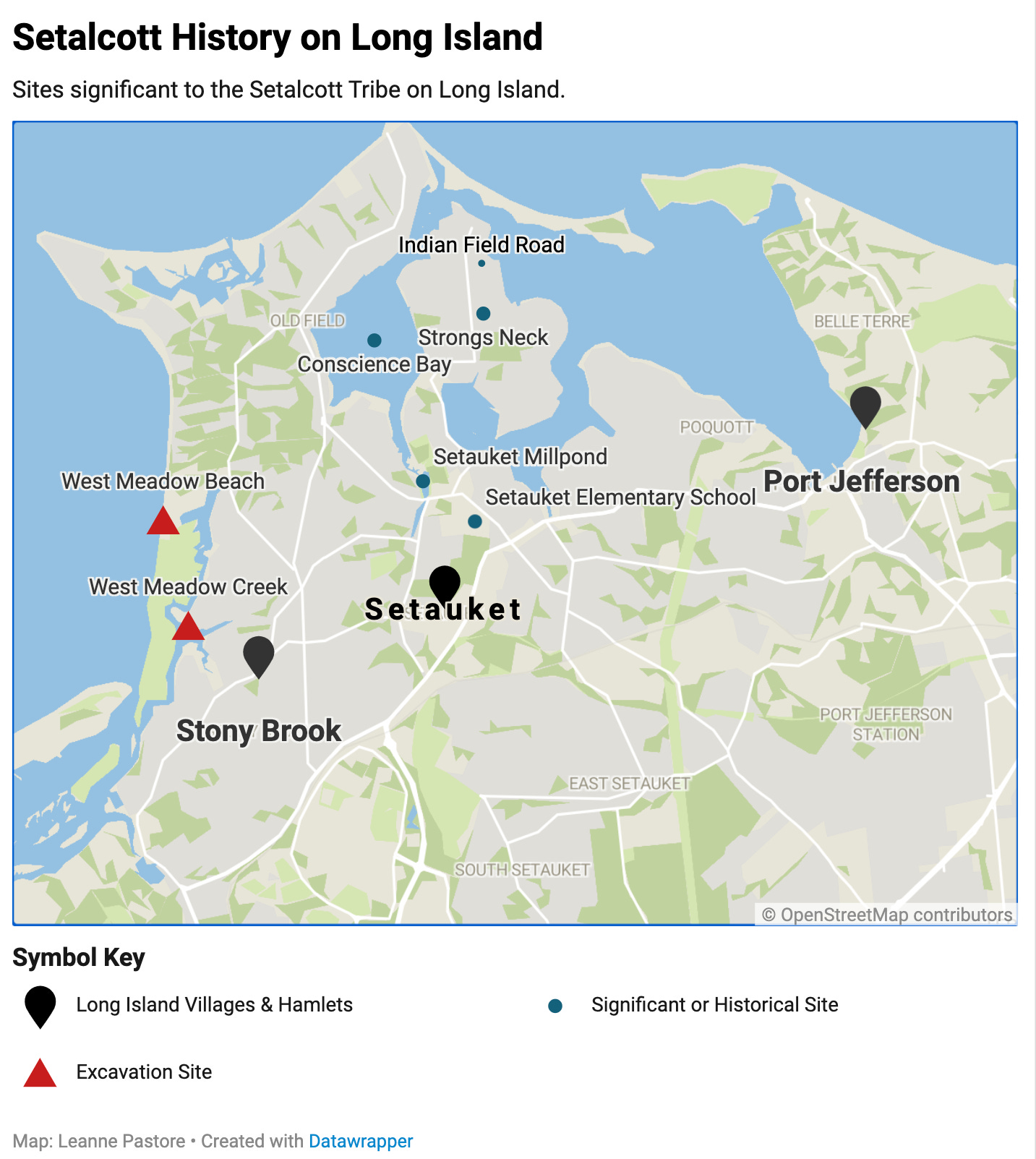

Setalcott history traces the tribe’s presence in the area now known as northern Brookhaven back to the end of the last ice age, approximately 12,000 years ago. Although Setauket was their central territory, they also settled in surrounding towns to the east — Riverhead and Southampton — and the west — Smithtown and Islip.

Kevin Sells, a descendant who embraces his role as a historian and archivist for the Setalcott, said his DNA reveals ancestry tied to migration across the Bering Strait: Insights which suggest tribe members traveled across the icy expanse that connected Asia and North America before arriving at the Eastern seaboard.

After the ice age, Long Island transformed into a hospitable environment: its mild climate and fertile soil enabled the Setalcott to thrive. The land yielded plentiful crops, with corn as a staple, and the surrounding waters, teeming with marine life, provided both nourishment and trade opportunities.

“Long Island turned out to be very supportive of human life,” Sells said, originally from Bridgeport, Connecticut, and now living in Tucson, Arizona. “It’s nicely positioned. The temperate climate was good for people who were used to it being very cold. The sea was full, and the [Long Island] Sound was particularly plentiful.”

Tradition and Cultural Practices

The Long Island Sound not only provided sustenance but also embodied the Setalcott’s spiritual beliefs, with the tribe’s sacred animals — whale, turtle, seal, and bluefish — central to their worldview, inhabiting the water.

According to Sells, the most significant of these animals was the eel. Descending from West Meadow Creek, the eel entered the Sound adjacent to where the Setauket Mill House in Frank Melville Memorial Park stands today. He added that tribe members worked in the Mill until it closed during World War II.

Eel skin provided the Setalcott with a unique, vital resource — leather, which helped ensure warmth during Long Island’s harsh winters. It also became a crucial commodity for trade in the late 1600 and early 1700s, as the material can be used to make boots, vests and purses. Sells said tribe members colloquially called themselves “the eel people.”

The tribe also made full use of the densely wooded area. Carving essential housing structures out of lumber protected them from environmental elements and wildlife. This included the framework of their longhouses, which Sells likened to the Māori wharenui of New Zealand. Sells believes that the Setalcott’s expertise in woodcraft likely influenced male tribe members’ later work in Long Island’s booming construction and shipbuilding industries in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

First Contact: The Arrival of Colonizers

The Setalcott were among the first Indigenous tribes to encounter colonizers on Long Island when settlers from New England arrived in Setauket in 1655.

On April 14, 1655, 15 Setalcott members, led by their leader, Warawakmy, signed a treaty with six Englishmen to sell land stretching from the Long Island Sound to present-day Mount Sinai, Belle Terre and Nissequogue. The document, signed by the colonists and Setalcott members remains displayed in Brookhaven’s Town Hall in Farmingville.

In the aftermath of this land transaction, tribe members were forced to adapt to the encroachment of their territory and its shifting dynamics, marking the beginning of a tumultuous era as the Setalcott people grappled with displacement from their rightful home.

“They bought about 35 acres,” Barbara Russell, historian for the Town of Brookhaven said. “The English settlers had the transfer of land for a price. The Native Americans did not have that same sense — they didn't know that they were giving up that land. So they lost that freedom to occupy the land as they saw, as they had before.”

With paper currency not in use in the United States until the 1690s, as a form of payment for the land, the Setalcott bartered six kettles, 10 coats, 100 needles, seven chests of powder, 10 wampum, a dozen hoes and hatchets, 50 metal drills, 10 pounds of lead and a pair of children's stockings, according to Brookhaven’s town records.

As colonizers continued to encroach, tribe members were relocated to areas like Minasseroke, also known as Little Neck or Strong’s Neck, where they formed bonds with other oppressed communities, which included Quakers and freed enslaved people. Sells recounts that Setalcott lore speaks of tribe members offering safe houses to aid the enslaved on their way to freedom.

This land transaction marked the beginning of a long struggle the Setalcott continues to face today as they grapple with the loss of their homeland.

A Battle for Recognition

After centuries of resilience, descendants of the Setalcott, like Sells, are dedicated to preserving the tribe’s history and culture. These efforts, like the annual corn festival and pow-wow at Setauket Elementary School, which the tribe has hosted for the past 16 years, expand beyond remembrance, but aim to educate Long Island’s youth. Sells expressed that Setauket’s local government has been nothing but supportive. Unfortunately, this has not been the case at the state or federal level.

Today, the Setalcott tribe fights for federal recognition, seeking to bypass acknowledgment on the New York State level. Sells said the tribe is looking to skip state recognition after multiple attempts passed through the legislature, only to be rejected at Governor Hochul’s desk.

Recognition at the federal level offers a tribe access to vital resources and affirms their sovereignty, which empowers them to self-govern without outside interference. It is a crucial step for preserving a tribe’s culture, as this ensures that descendants of said tribe can continue to practice and celebrate their ancestral traditions for generations to come. For the Setalcott, this would also mean restoring their land in Setauket.

Achieving this status is a formidable challenge that requires time, dedication and persistence to navigate bureaucratic hurdles. This arduous journey was exemplified by the Shinnecock Nation, which finally received federal recognition in 2010 after tirelessly fighting for three decades.

There are currently only 574 federally recognized tribes in the United States, with the number of federally recognized tribes in New York relatively small, at nine — a stark contrast to Alaska, with 229, and California, with 110 —– the two states with the highest number.

Meeting the stringent criteria set by the federal government has resulted in many tribes across the country, including descendants of the Setalcott, continuing to face challenges to obtain rightful acknowledgment. However, in spite of the difficult journey ahead, they remain steadfast in their pursuit to reclaim their rightful space on their ancestral lands.

““My goal is to see us amass some land,” Sells said. “We are literally being priced out. Our elders can’t afford the taxes on their properties. So, I would like to see us be able to get enough continuous land to put into trusts for the tribe, so we always have a place there.”